Our Spotlight series highlights people who helped create the world which we are stoked to live in. Their deeds forged the pathways of our beloved lifestyle. We selected Mr. Backlund for his talents in woodworking as well as his skill on the river. Enjoy the tale of a true river artist, by Editor-in-Chief Mike Toughill.

IF YOU HAVE EVER handled a Backlund paddle then you know… There’s something different about them. Something beautiful and loving. Something transcendent there. Something REAL.

THE MAN

Keith Backlund was an artist who breathed life and love into his work. His paddles were handcrafted with tenderness, formed specifically with each individual in mind, constructed with love of the wood and respect of the forest as well as love of the art of paddling and respect of the river. They are show pieces, but rather than being built to hang on a wall, they were built to last on a river, to paddle and power and SURVIVE, just like the paddler him or herself.

Keith was an easy going guy. Sipping Crown Royal with him at The Pub in Ohiopyle, PA you might never know you were in the company of one of the most famous, sought after paddle makers in the world. But soon, his love for his work would show through, and he’d tell you about it. Not in a bragging way, but in a gentle soft sort of way. Humbly he explained that he selected his wood from one particular hillside in the Adirondacks in upstate New York, on a particular half acre slope, from a specific stand of trees chosen because of their age and quality and the way the sun hit just right. He was exacting as a scientist, but preferred the insights of the artist in his conjuring of paddle from tree. His techniques were measured and repeatable, like the way he sized each handgrip to the hands that would perform the work. Yet he breathed art and life into his creations, realizing that paddling was much more than numbers and processes. Still he improved by applying discipline, just as he used discipline to become a top paddler back in the days of his youth.

But you never would know all of this sitting beside him, watching the rain fall in sheets outside. Instead he’d share small river stories, be gracious and quick with a smile, never assuming, friendly with all, even a stranger from out of town like me. You might not know about how good these paddles are (it’s hard to imagine that some of them won’t be on the water for years to come), or how he had come to make them, about how he had competed early in life, how he was a bomb boater who had sunk his life into it. I didn’t. I only knew then that this older gentleman WAS COOL. In the true sense, meaning that he was warm, soulful, present. And so, we had another drink.

PADDLING WITH KEITH

I try to make it to Ohiopyle, PA once or twice a year to paddle the Lower Yough. I grew up not far from there, and have memories of getting ice cream as a little boy over at Falls Market. The Lower was the first whitewater I ever paddled, with Whitewater Adventureres, as a customer. One trip and I was hooked. And many years ago I also met Keith Backlund.

I remember the last time he and I met. It was early evening in the middle of summer. A friend and I were in town to paddle and camp for a few days. I brought many people over the years to this my favorite destination out East. It was always the same: marathon drive, then a week or so of Nothing. But. Paddling. We’d only drive as far as the takeout. Totally immerse ourselves in the River and the Community.

That was just such a day. We’d done the full run earlier, and we were set to head home the following day. There was still an hour or so of daylight… So why not? We headed down to the beach to put in and get one last fix, a Loop run.

There was Keith. Although I’m not sure he exactly recalled my name, he recognized me, and we chatted. He was getting into his boat, with his old school helmet and his amazing wooden paddle. I remarked that I hoped to get one next year, that I’d been eyeing a used one for sale over in the Trading Post barn. “You’ve got to get one from me,” he said. “I’ll make it perfect.” I knew what he meant, and that he was right.

The three of us paddled the Loop together, mostly in silence, sharing some smiles, a couple one liners and a few sentences in eddies, playing a bit in Entrance, choosing our own adventures in Eddy Turn. I followed his lines a few times, and remember remarking to myself how fluid and smooth Keith’s style was. I recall consciously telling myself I wanted to paddle like that. Previous to that I charged pretty hard. Since then I’ve strived to also be fluid.

That was 2008. I hadn’t seen him in a year, and little did I know I wouldn’t meet him again. He had a careworn look that I hadn’t seen before. He invited me up to his shop. I wish I had gone. But I chose to be hurried by responsibility. I regret that. I never got a Backlund paddle.

I didn’t know how stellar a paddler Keith was, other than from that one time together on the Yough, until I heard of his passing and read about his life. Like most of the dirtbags of his era he started in canoes. He raced with his brother, paddling the Delaware and other rivers in the Pocono Mountains region of PA. After getting Wallaced in a hydraulic paddling flood stage, and getting helped to shore by a kayaker, he determined to get a kayak himself. His art teacher drove him to New York City, where he purchased one for $260. He was one of the only people in the area to have one.

Keith really got into paddling, like everything in his life he wanted to master it, and like a true dirtbag he was obsessed with the river. He got into slalom kayaking, which was all the rage in those days. He started using a wooden paddle like the Germans, who were the best in the world. However, he couldn’t afford a German paddle, so he bought a cheaper paddle which broke right before the Down River Nationals on the Lower Yough in 1972. He later was quoted, “I had a really short fiberglass paddle for the race. I think to this day that I might have won if I had my wooden paddle, but I fell over at River’s End and had to roll and lost by thirty four seconds. Shoulda-woulda-coulda. If I had my wooden stick that wouldn’t have happened! I found my silver medal from the Lower Yough in 1972 the other day in my tool box. I got beat by a guy named Tom McEwan,” of the famous McEwan family of paddlers known throughout the world. Keith truly was a terrific boater!

He had learned woodworking from his grandpa growing up, and started making his own paddles. In the winter of 1973 he moved to California to train for the Championships, running rivers and selling paddles to make ends meet. He barely missed making the Worlds team, and returned back to PA broke. Keith moved to Ohiopyle, becoming one of the first safety boaters on the Lower Yough for WWA. He was there at the beginning, quoted saying “so I’ve seen the whole guide scene evolve and change.” To the end of his days he jokingly described himself as a recovering river guide. He was always joking.

Keith was a creeker when creeking was brand new. In the early spring of 1978 Keith and James Harrington Bruno scored a 1st D of the Toxaway – in 13 foot fiberglass boats! Sure, they portaged a ton of stuff, taking three days to complete the mission (a stretch that didn’t get regular visitors until the early 2000’s) but once again Keith wasn’t just a paddle maker, he was a paddle monster. He didn’t create his paddles to be hung on walls, he made them so he could run THE SHIT.

He was a major impetus for the first UY race, along with Jim Snyder, Jess Whittemore and others, donating a paddle to whoever took 2nd place (Jim Snyder built a Slice for the winner). What a prize package!! A custom Backlund paddle was the top prize for several years after that.

Even after his stroke he was out running the river, taking his family on raft trips down the Yough. This was his home. This was his passion. He dumped it at Dimple one time, I’m told by a dirtbag friend who was there. Keith never gave up on paddling. It was his life.

Paul Schreiner, another true whitewater artist and legend of the local paddling scene that developed in and around Ohiopyle and Friendsville in the 70s, made a composite slalom boat specifically for Keith, the “Extreme.” One artist contributing to another, both with the same individual handcrafted style to their creations. This all developed from being there when our sport was BORN. We owe so much to these guys.

Meghan Reilly, whom I met many years ago when she was pushing rubber at WWA, later worked for Keith in his shop. I asked her about paddling with him. “Keith worked on paddles more than anything else while I worked with him. We did get out for a January snow paddle once and many attaining trips in the warmer weather. Keith and I attained from the Middle Yough take out and he invited any other females to join us. His paddling and teaching were all about being smooth.” Damn straight.

THE PADDLES

Keith Backlund didn’t just MAKE paddles, he breathed life back into the wood and fiberglass and CREATED them. He approached his craft not only from the standpoint of a paddler making the best tool possible for his own recreation, but from the angle of the master woodworker forming a piece of functional art.

He loved to create custom paddles, which naturally evolved into the formation of two mainstream paddle companies, Woodlight and Viking. His apprentices would include three paddling legends: Phil Coleman, Jim Snyder, and Jess Whittemore, all whom credit him with being “a catalyst for excellence.” His fundamental teachings in craftsmanship, his unique techniques and design, his focus and even his humor would color their development and further enrich our community.

Keith was a wood carver since age seven, making ax handles for his grandfather. The old man was a lumberjack in the Adirondacks all his life. The handles were so good, all his friends wanted one, and by age 12 Keith was making ax handles that sold for twice as much as store bought ones. This is how he began his career as a master woodworker, and how he learned his love of good wood, from his grandpa.

Keith began making paddles because he couldn’t afford one. When he first started, the doubters told him that only European craftsman could make a good wooden paddle. All of the top paddles were coming from Germany and England. At that time Toni Prijon was the best, making the finest paddles in the world. Keith, himself a perfectionist, wanted to make an equally renowned product. The reputation amongst the slalom boaters was if you owned a Prijon paddle, you were awesome – just because you owned a Prijon paddle. Toni Prijon hailed from Slovenia, which probably had in that era more world-class paddlers per capita than any other region in the world. They possessed a distinct advantage of having world class Alpine whitewater there, and a strong racing tradition.

Prijon was everything Backlund wanted to become, a top boater who also made his own gear. When he had first started out, he took a job at Klepper, which happened to be the first kayak Keith owned. After winning the Down River Worlds in 1959 he moved down the street and started Prijon Boat Works quickly becoming a world famous boat builder. Prijon kayaks won more slaloms and down river world championships than any other in the world, and this was the type of reputation Keith aspired to: top quality greatness.

While racing and making his own paddles, Keith met Dave Mitchell, another paddler in the tight-knit racing community. Dave took the silver medal in the 1972 Worlds, and apprenticed with Toni, learning how to make European style paddles. He then traveled all over Europe trying to find wood to make paddles out of, but eventually moved back to America, settling in New Hampshire because of the abundant supplies of good wood. Keith wrote asking if he could come and get work in their shop, receiving a little note in reply, saying ‘At this time it would economic suicide to allow you in our workshop.’ Mitchell is still producing paddles in New Hampshire today. Although sturdy, they aren’t Backlunds.

Keith had figured it out all on his own. He made his first paddles, the “Dagger,” while racing the kayak slalom circuit in the early 70s. These paddles weren’t strong, lacking the fiberglass reinforcement and top quality woods that a Backlund paddle would become known for. After Keith married in ’74, he settled down outside State College, PA (where he had attended Penn State) and launched Woodlyte Paddles. Woodlyte went under in ’75 after an associate promised the entire US team headed to the World Championships in Yugoslavia a free paddle. The resulting rush to complete over 40 paddles led to delamination problems and much breakage. It was around this time that a young Jim Snyder began his apprenticeship with Keith. Keith also tried using a multiple paddle carving machine called the Butch, which he then abandoned after seeing it would never produce the high quality blades he wanted to be known for.

Bill Masters, founder of Perception (a new company at that time) offered to back Keith, and the growing Backlund family moved south to Easely SC. Not long after he left Perception to start making Dagger Paddles with Brandy Leeson, putting fiberglass over it instead of the standard veneer. Dagger later transformed into Dagger Canoes, designing boats based on wood strip canoes made by Keith.

He pioneered working with fiberglass in paddle construction, discovering epoxy coating in the early ‘70’s. Prior to this innovation cheaper polyester resins were the norm. It didn’t have the superior properties of epoxy, and when Keith realized this he refined the process and changed wood paddle making as we know it today. His paddles regularly lasted 10 or more years, unheard of before his technique was developed.

Backlund paddles are perfectly balanced for weight, flex, and feel. Keith carefully chose the lumber, using curly maple, curly willow, ash for strength, spruce for a lightweight core, beachwood, and curly sycamore on the ends. One piece would be folded over and used on both sides of the blade, allowing it to vibrate symmetrically instead of flutter. Where other companies would randomly select different pieces of wood of the same species, creating a vibration differential across the blade, Keith refused to compromise. No matter how well shaped the composite paddles were made, they fluttered. Keith once said, “Whoever buys a paddle gets my best craftsmanship.”

“At one point, I wanted to be the Prijon of American. Now I know that it is much more fun to be the Backlund of America.” Keith produced high quality kayak, freestyle, and RG (raft guide) paddles, and his top of the line paddles, using curly willow from New York, ran $1000. “It’s extremely rare. I bought twelve thousand feet of it and only three boards in that 12,000 feet were curly.”

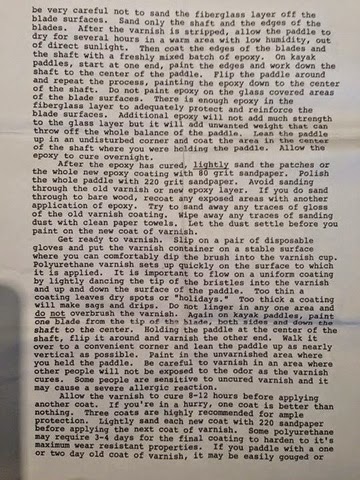

Jess Whittemore’s Backlund repair kit with type-written care instructions

Meghan remembers working in Keith’s shop in the later years. “Keith was not afraid to remind anyone doing anything in the shop, do not bleed on the wood. Knives were kept sharp.” Keith had a passion for making knives also, the tools he employed to shape the wood meaning as much to him as the art itself. He was born and raised with wood, and lived a life of paddling. His art was the natural outcome of the marriage of these two.

LEGACY

Keith Backlund left this world richer than he found it, filling it with his patient handywork and his passion for those people and pleasures that he loved. The memories of the time he spent with those of us lucky to share in his love fill the heart with a good vibe.

Meghan Reilly shared one with us. “While working with Keith, we always cranked the radio a little at 3pm on Fridays to listen to the Hubba Hubba song. Funny little song about a Happy Boy, with a twist.” His humor will always be remembered. He had an understated deadpan delivery to his quips. Take for instance the “Duck Foot Paddle,” shaped like a duck’s foot in classic Keith fashion. “If you are not careful paddling with this, you might quack up,” he told Marci Lynn McGuinness back in 2002. “You’d have to be crazy as a loon not to try one… It cost several bills. What kind of wood are we going to put on the tip? Bird’s eye maple!” And he was an astute observer of the various social combinations in the super small river-town of Ohiopyle, who would famously remark as each new relationship made the gossip circuit, “Seems like the parts fit.”

Jim Snyder shared a few thoughts with us on Keith. “Keith was always a good humored fellow with a penchant for puns, as well as short ditties which he might break into at any moment. And he did really funny impersonations as well. His New World paddles set the benchmark for quality and craftsmanship and he had a number of apprentices throughout his career. He was always open with sharing his knowledge of the craft and is considered the godfather of wooden whitewater paddle manufacture in the United States.

Keith had a colorful history with many of the movers and shakers of the sport way back in the day including Joe Pulliam, Steve Scarborough, Bill Masters, and Tom Johnson among many others. But people probably remember him best from one or more of the many “Backlund stories” that peppered his career- like the time he ran the Albright dam- at midnight- drunk- without a sprayskirt… that didn’t go well. There’s lots of stories like that. Keith knew well you’ve got to make your own fun in a small town. I’ll always remember him as a kind and generous friend with a ‘sharp’ intellect and sense of humor.”

Keith’s wife Ann also remembered how patient Keith was, both in the wood shop and on the river. “Sometimes he’d tell me so much I’d have to say, “Ok, Keith, that’s all I can handle,” she fondly recalled. “His patience was amazing, and he loved to teach others.” They shared walks in the woods, and Keith would entertain her with his knowledge of the trees and the doings of the forest. “Keith loved wood.” When she looks into the sky at night, Ann sees Keith in the constellation of Orion, standing in the wood shop, balancing a paddle. “He would swing it, carefully getting the paddle perfectly balanced,” she recalled, getting all of the various wood pieces together to make one harmonious instrument of love. Keith sought and attained perfection in his art.

He has been honored with a piece of art, so befitting a master artisan, with a sculpture by master statue builder Jamie Lester from Morgantown, WV. It is located in the town park in Ohiopyle, PA, and is loaded with meaning. Jim Snyder explains the rich symbolism, something Keith would love: “Keith’s memorial represents a stump growing in rocky soil- to show his rugged early life and the fact that he is rooted deep into our sport. And then the stump is sculpted into a model of a knife handle keith carved- he loved his knives and loved to carveknife handles. At the top- a Backlund Slasher blade emerges from a pool of water- a blade shape Keith perfected and probably his most popular shape. On the blade face Keith’s face is engraved and when you look at it just right you can see the reflection of your own face superimposed on the etching of Keith’s face- because his paddles were where he ‘interfaced’ with the public. Keith always loved terrible puns. And if you look at the roots of the tree- you can see an impression of his foot- because he really left his footprint on the sport.”

Keith Backlund, master woodworker, innovative paddle maker, river guide, slalom racer, story teller, teacher, prankster, family man. A true Spotlight of our sport. We leave you with a few more quotes of his. “The enemy of quality is quantity.” “Turtlin’ along…” “I must, I must, I must make the dust.” “Step Good.”

Ann said simply, “I miss him.”

Jim Snyder on selecting wood with Keith

Keith was highly involved with the Yough Riverkeepers, and this river was the blood thatpumped through his heart. Please consider making a small donation of time, money, or support

POST SCRIPT: Dave Kersey owned the Paul Schreiner slalom boat made for Keith, and a Backlund paddle, hung lovingly in his living room. Dave once said, “I didn’t know Backlund. After I bought the boat from Paul I had mentioned toMike Moore and Kevin ONeil that I wanted to meet him. They thought it was a great idea and were going to arrange it next time we were out Keiths way. Unfortunately Keith passed before it could happen.

Those who enjoy the history of our sport and are able to meet/befriend the individuals who have defined and pioneered it, are so blessed to have had those experiences. Of course, written articles and video documentaries are nice but obviously no substitute for history heard in person from those whowere there.”